England's Positional Play Issue: Some Thoughts on the Tactical Evolution of the England National Team

Southgate's England attempted to imitate the form of the elite teams, without committing to their underlying principles

Until that night in Dortmund, England’s latest Euro campaign was again a source of controversy among the fanbase. The group stages were marred by tedious debates over Trent Alexander Arnold’s positioning in midfield, the absence of young players such as Cole Palmer or Kobe Mainoo in the midfield, and whether Jude Bellingham is a 6, an 8 or a 10 in this England system. Kane for Watkins; Wharton for Rice; Shaw for Trippier the ‘pile on’ was indeed in full flow. Yet while these excruciating debates dominated the TV airwaves and broadsheet papers alike, they distracted many from the real underlying problems of England’s tactical approach. These speculative debates about incremental tactical adjustments are adiaphorous considering the broader structural problems associated with the national team throughout the tournament and indeed in previous tournaments. England reaching the final should not defer a serious reassessment of England’s game model, principles and delivery of the so-called ‘England DNA’ introduced by the FA’s former Technical Director, Dan Ashworth in 2013.

A short disclaimer before beginning - I am not of the school that believes Gareth Southgate is tactically inept. This is not a tabloid-style polemic against the qualifications of a man who is clearly qualified to coach at the very highest echelons of the game. He will land a big job (if he wants one) and I am sure will succeed. Mainstream pundits and journalists must remember - these coaches know a lot more than you! A fifteen-minute conversation with Southgate (or any professional coach for that matter) with his tactics board open would leave any critical Guardian journalist gasping for air. Southgate played over a decade in the Premier League, represented England at the very highest level and has an intuitive feeling for the nuances of the game that critics outside of the arena simply will not be able to comprehend. Southgate has an idea of how football ought to be played and he possesses the coaching ability to transmit this idea to an elite group of players. Football analysts must always keep Cruyff’s dictum in mind:

‘There are many people who can say that a team are playing badly. There are few people who can say why they play badly. And there are even fewer who can say what should be done to make them play better.’

The question however is less the coherence of this idea than it is the viability in the context of modern football. Even the casual football fan could observe during England’s first few games that something was not right. England did not move the ball with the fluidity of the Spanish or press with the aggression of the Germans. They could not move the ball back to front with the precision of the Dutch. Games were turned by moments of individual brilliance, inevitable from a squad stacked with elite talent. But why was this the case – and what is there to be done?

I contend five key principles are exhibited in *almost* all elite football teams in the modern age, regardless of systems or tactics. These principles often fly in the face of the 1990s to early 2000s orthodoxy that many national teams (not just England) still operate under.

1. Positional Play

Positional play is a concept that is ubiquitous in coaching discourse but almost unheard of in the popular sphere. It’s also an ambiguous concept with a range of meanings. Some claim it’s an empty trope that does not mean anything. For the sake of simplicity, see it as the operating system of football, Windows, or iOS. It is not a tactic, but a set of assumptions about space, time and movement on the football pitch that provide a framework for tactics to be developed within. The premise of positional play is that you control the game by controlling space via structured occupation in geometrically organized rooms or zones.

(The 18 geometrically ordered zones in positional play)

With its origins in the teams of Johan Cruyff and Arrigo Sacchi, this modern iteration of positional play was perfected by Pep Guardiola but has been adopted as the basic framework by coaches as diverse in their ‘philosophies’ as Jurgen Klopp, Luis Enrique, Xabi Alonso, Thomas Tuchel, and Julian Nagelsmann. Positional play is the methodology adopted by all elite possession teams, most famously Man City and Arsenal. In the Euros, Spain, Belgium, and Germany exhibited clear positional play principles. Emerging coaches such as Fabian Hurzeler and Nuri Sahin also adopt such an approach in their game models.

Gareth Southgate was of course not oblivious to this. No UEFA Pro-Licence coach would be unaware of the cutting-edge methodology. Yet the process of adopting such an approach has its risks. An extremely high level of detail orientation is required from the head coach and his team. A solution needs to be derived for every potential scenario, both in and out of possession. Technical supremacy is required in every game - fine against Slovenia, Slovakia, Denmark but could this be guaranteed against Spain, Germany, or France? He simply made the decision that a more orthodox style would suit his tactical disposition and the technical disposition of his players.

Having said that, the majority of England’s starting line-up and main substitutes already play under positional play methodology at the club level (Kane, Foden, Stones, Walker, Rice, Saka, Alexander-Arnold, Watkins, Guehi, Wharton). There is no reason why England cannot and should not play and think like protagonists.

England half-heartedly adopted a positional play approach. But to modify Ralf Rangnick’s famous adage on pressing – ‘a little bit of positional play is like a little bit of pregnant’. What does this mean? Have a look at the image below.

(England’s 3-5 build-up shape vs Switzerland in the Quarter Final)

Look how the England players are organised. There is a clear positional play logic to their shape. Saka and Trippier occupy the two wide channels. Kane and Mainoo are occupying the half-spaces, and Bellingham is playing in the central channel. Rice and Walker are occupying the two central zones to form a line which is part of England’s ‘rest defence’ shape (another core positional play feature). Foden is filling in to constitute the third deeper player behind the ball to create the three-man ‘lock’. If Saka were to lose possession England would be in decent shape to stop any potential counterattack from Switzerland.

This is an exhibition of an element of positional play. Yet why do I refuse to still classify England alongside Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, and Belgium as a genuine ‘positional play’ team?

Have a look again at the image and notice the problem here. Switzerland have responded to England’s front 5 build-up structure by playing with 6 men in their defensive line. There is now no overload for England. The whole purpose of positional play is to create numerical or qualitative superiorities to unbalance the opponent in every game phase. England had no plan, no in-game adjustment to unbalance the situation. Instead, when the roadblock was met, England resorted to playing deep crosses and long balls, hoping one of them would come off.

We must go back to the words of Ron Greenwood to unpack this one. For context, Greenwood was the legendary coach of West Ham United in the 1960s and early 70s. He led the team to their first two major trophies in the club’s history – the 1964 FA Cup and the 1965 European Cup Winners’ Cup. He also produced three of the most important players in England’s 1966 World Cup win – Bobby Moore, Geoff Hurst, and Martin Peters. Notably, Greenwood was enamoured by the football tactics he was witnessing on the continent, taking his West Ham team abroad regularly to learn from those at the cutting edge of the game. He was particularly fond of the West Germans and the Hungarian styles. Yet he was voracious in his criticisms of those who tried to imitate these continental playing styles without the underlying understanding of why such a style worked.

‘Hungary played in triangles, many tried to copy them but what imitators used were static triangles – the Hungarian way was different – they used moving triangles – much more difficult but infinitely more effective – their players were constantly changing – their style was all about understanding, rhythm and intuition; all linked together by the lovely skills of the Hungarian players, the effect was devastating’.

Greenwood’s observation about the English attempt to adopt Continental tactics is as prescient today as it was forty years ago. England under Southgate appears to be trying to mimic the form of positional play without internalising its underlying principles. Positional play is more than simply dividing the pitch into eighteen zones and using this map as a reference point for occupying space.

It is what you do within such a map that enables the methodology to work the way it is intended. The four corresponding principles can be regarded as subsets of the broader positional play logic.

2. Vertical Compactness

Vertical compactness is the amount of distance between the last defender and the striker. The more vertically compact you are, the easier it is to recover the ball out of possession and play sharper, quicker passes in between the lines in possession. A hallmark of all top teams is displaying this compactness. This applies both in possession and out of possession.

Vertical compactness is also a prerequisite for executing a strong high press. The centre-backs need to be high up the pitch, to close space and prevent the opposition from finding space in the middle of the pitch easily if the first line of pressing is unsuccessful. In the words of Jose Mourinho – ‘it’s just a basic principle’. In football nomenclature, the somewhat ambiguous terms of ‘low block’ (how an archetypical Jose Mourinho team plays against the ball), ‘mid-block’ (how an archetypical Pep Guardiola team plays against the ball) and ‘high block’ (how an archetypical Ralf Rangick team plays against the ball) have all permeated popular discourse. What all these blocks have in common is that they create compact defensive structures. They all serve the same purposes.

Take a look at Germany’s shape against the ball in their game against Denmark.

(German vertical compactness against Denmark)

This is nearly a perfect example of vertical compactness against the ball. If anything, Fullkrug should be slightly deeper in line with Havertz, but as you can see in the picture, he is correcting his positioning by the necessary 3m (details matter). The German defensive line of four is high and this is compounded by Havertz and Fullkrug, Germany’s two highest players, dropping in.

What is happening in the sandwich between the defensive and offensive lines is also a typical feature of teams that exhibit vertical compactness. Rather than playing with a flat midfield line, the middle players against the ball are staggered, making it harder for the opponent to find space in between the lines in phase two (technical term for the progressing of the ball through the midfield).

Now compare this to England’s out of possession shape.

(Problems against the ball for England in the Final)

The contrast to Germany’s off the ball discipline is astounding. First, the distance between Watkins and Guehi is far too great. The distance between Watkins and Palmer is also far too great. Not only is England’s back line far too high up the pitch, making it easy for Spain to progress into the midfield but England’s two midfielders (Rice and Bellingham) are also far too deep. The England players are disorientated. Olmo has all the space he wants in between the lines to receive, turn, carry the ball, and find the dangerous wide players. The box-defending quality of the England players is very high. This is what saved them and saw them progress to the final rounds of the tournament in spite of these clear structural flaws.

It does not take an expert to see this when contrasted with Germany’s shape pictured above. The real issue is why this was the case. England probably had a plan to drop deep and be compact, and it could be argued this frame is a red herring. It’s 85 minutes into a European final. England have been chasing the game. Just before this frame, they had thrown six men forward to find a second goal. England, of course, possess elite defenders.

But I think this is a let-off. This was not the only instance in the tournament where England, with their deep defensive line, struggled to control space in between the lines and stop their opponent’s build-up play at source.

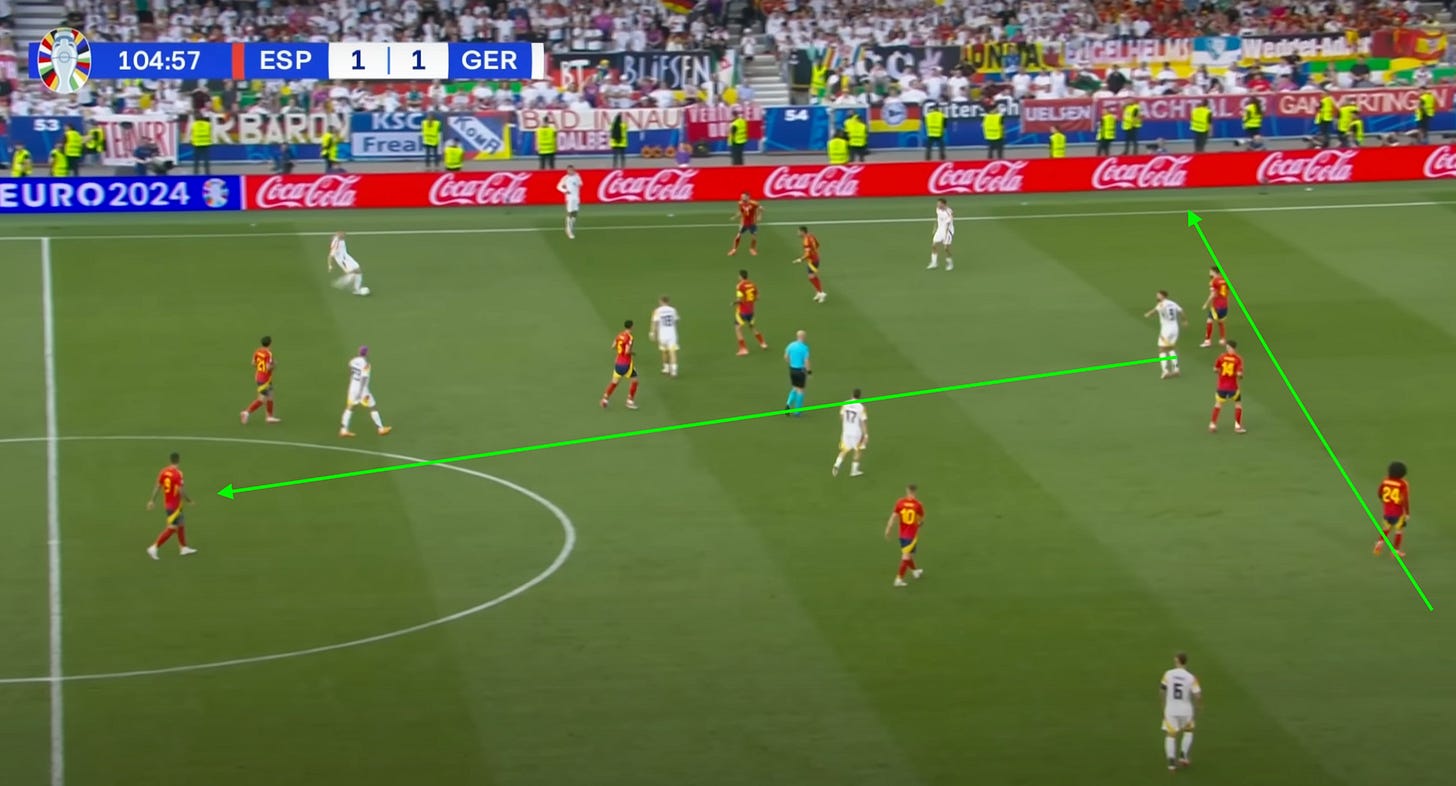

Contrary to most pundits, this was not just due to a lack of pressing (although pressing was also an issue). It was in fact due to England players continually being disorientated in defensive transition. They were disorientated due to a lack of clear reference points. This once again goes back to the half-hearted application of positional play principles. Even a team known for its offensive dominance, Spain, demonstrated a far more structured against the ball set-up, even deep into extra time, very similar to Germany’s.

(Textbook example of Spanish vertical compactness against Germany)

Positional play is not just an offensive concept. It is a vital frame of reference for defensive positioning. However, if the methodology is only implemented partially, it will fail to permeate the deep minds of the players. In moments of high stress, physical exertion and high adrenaline, they may lose their way, and resort to safety-first instincts which is to drop deep and try to protect the box at all costs.

3. Shorter Passing Distances with Fluid Rotations

Vertical compactness again is not just a defensive principle. It also has great offensive benefits too. The consequence of vertical compactness is shorting passing distances between the players. This enables teams, in possession, to execute intricate passing combinations that commit opposing players and take them out of the game. The closer the distances between the players, the riskier the passing combinations are. However, the riskier the passing combinations are, the higher the potential there is for devastation.

In some coaching circles, particularly those in the English school, the comically botched trope of no ‘tippy tappy football’ (seemingly a product of the inability to verbalise the word tiki-taka) has been thrown around. There is even a podcast named after it. Yet the tactical trends in modern football suggest that short passing is not only more aesthetically pleasing but actually more efficient than a longer passing approach.

This chart below is telling.

There is a clear correlation in this table between the team’s league position and their ability to engage in short, intricate passing combinations. This does not mean every pass has to be short. But the short option should always be the first option.

Shorter passing distances are the way forward in modern football. It was the best weapon to unlock increasingly organised and compact defensive structures. It is also a very necessary tool in a team’s tactical arsenal to evade pressing. Pressing makes the spaces on the pitch within which a team can play increasingly smaller. Whether teams like it or not, they have to be comfortable on the ball in tight spaces.

The obsession with pressing in the modern game can also be counteracted by a team that is comfortable playing on the ball in tight spaces. A team comfortable playing short passes in tight spaces can engage in ‘press baiting’. The most radical example of this is exhibited in Roberto de Zerbi’s Brighton team, who are willing to hold the ball and park their players in a stationary position for up to thirty seconds until the opponent loses their patience and jumps. It is exactly what Guardiola is referring to in that famous changing room clip in the Man City ‘All or Nothing Documentary’.

Germany’s build-up play exhibits these qualities. It is not just an exclusive quality of the so-called Spanish ‘tiki-taka’ style of play.

(German positional play against Denmark)

Rudiger demonstrates the art of press baiting in this situation. He only plays the ball they Hoylund and Eriksen engage the press. He is assisted with three clear passing options, in close proximity. There is a lot to unpack in this rotation alone. Just look at the starting positions relative to where the players are ‘supposed’ to be on the pitch. Kimmich the right back has rotated into the holding midfield position, directly in front of Rudiger. Can, the holding midfielder has moved into Kimmich’s right back position. Kroos, who conventionally played as a third man in the back line in the build-up play due to Denmark only pressing the German defensive line with one forward player.

Now take a look at what happens next after Rudiger plays the ball into Can.

(Intricate German passing rotations in the progression phase against Denmark)

Like magic, the wide ball to Can is a decoy to force Hoylund and Eriksen to press. Kimmich immediately receives the short pass from Can and turns to find Kroos who is now the spare man. Germany continues to move the ball into the middle of the pitch, completely bypassing Denmark’s press.

This rotation was not intuitive. It was diligently choreographed by Julian Nagelsmann before the game who had clearly studied the Danish pressing structure. The Germans were not afraid to play risky short passes in deep areas of the pitch in order to bypass the Danish press. Going long when stuck was only the last resort.

Once again, the positional play approach is to thank for this move. Players were able to move into their pre-determined zones, all in perfect unison because they had all internalised positional play principles, drilled into them by the German coaching team. Once again, what it must be remembered that what is so dangerous with positional play is not your starting point, occupying certain zones rationally, but the movement from zone to zone, based on pre-rehearsed routines (think back to Ron Greenwood’s ‘moving triangles’ idea). These rehearsed routines were procured specifically to bypass the specificities of the opponent’s pressing structure.

It is not the case that England does not want to play through the phases and build from the back. Like every elite team, this is their exact intention. Yet they seem to come across more roadblocks than Spain or Germany did.

(England’s passing distances were too great against Slovenia)

This was the story of England’s build-up play for the majority of the tournament. Guehi has two passing options, and no line-breaking pass on. He also rushes the pass, without there being any clear press-baiting strategy.

England’s build-up play throughout the tournament simply mimicked the aesthetic of how the elite teams play, without internalising the essence of why these tactics are executed in the first place.

At the bottom of the picture, there is Foden making a deep run, interchanging positions with Walker. This is an attempt to execute a positional rotation in order to find a spare man. Just like what Germany did in the picture above. However, it had nowhere near the intended effect. The distances between the England players were far too great to commit the Slovenians to press the ball. Instead, they dropped into a deep 3-4-3 shape and simply let England sluggishly move the ball into their block. There was no temptation to press as the England players were so far apart. With the Slovenia players so deep, it was difficult to unbalance their structure through a rotation.

It is not just in the build-up phase or progressing the ball through the midfield that short distances between your own players are a benefit. The image below highlights the power of short distances between players can have when attacking the box. Rather than having a target man in the box, and maybe one or two late runners, as conventional football tactics will advocate for, Spain has six players in close proximity to each other in the box, and two dropping in behind.

(Spain’s players were within 5m of each other in the box against Georgia)

Now contrast this to the distances between the players in an England game in an almost identical situation (both teams are 1/0 down and have the ball in the offensive left half space).

(Too far great a distance between Saka and supporting players for England)

England only has three players planted in the box, with a late runner (Palmer) supporting off the edge. The lack of players in passing positions close to Saka forces him to play a hopeful cross into a box, which is already flooded with Slovakian defenders. While one in every fifteen of these hopefully crosses may pay off (as it eventually did for Bellingham’s goal), this surely is leaving too much to chance and individual quality. England also has the quality of players who can play in tight spaces (Foden, Palmer, Bellingham, Mainoo, Saka).

4. Counter-Pressing

Counter-pressing is perhaps the most well-known concept in popular football discourse. It is the process of winning the ball back as soon as you have lost it, by chasing the opposition down. The premise of counter-pressing is that the opponent is the most vulnerable in possession in the first three to five seconds of gaining possession. Therefore, rather than immediately retreating to your defensive shape as soon as you lose the ball, exponents of counter-pressing argue that you must win it back as quickly as possible.

(Spain’s relentless counter pressing in the final against England)

Spain mastered the counter-press in the tournament. Swarming the ball receiver within one or two seconds of receiving the ball, typically engaging four men in the press. Spain’s love for playing the ball in tight spaces, via short passing combinations, enabled them to turn a successful counter press into a successful phase of possession.

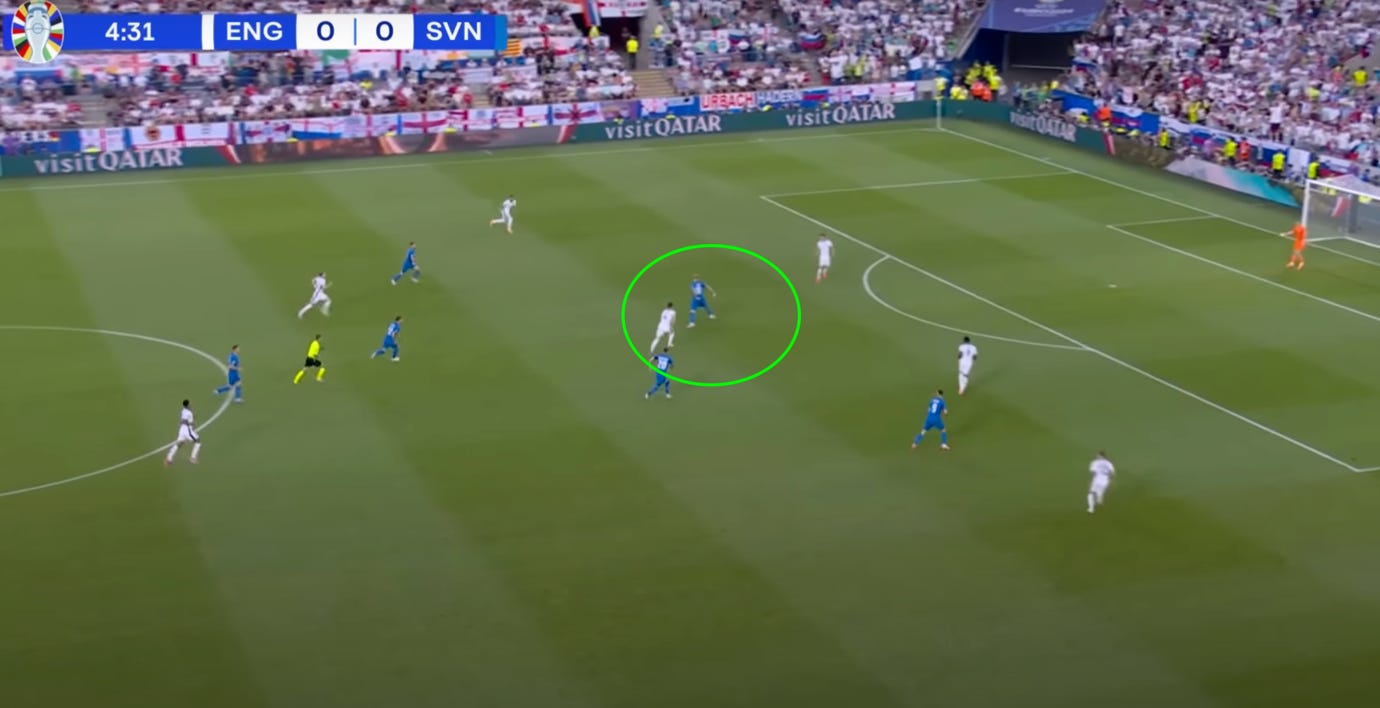

(England’s struggle with counter-pressing against Slovenia)

Contrast this to England’s attempt to counter-press Slovenia. The problem is that the distances between the England players in possession. There is a reason England were not able to regain the ball with the same efficiency. Let’s go back to principle 2. Short passing distances.

The shorter the distances between the players in possession, the easier it is to release the counter-press when out of possession. The 10m to 15m passes England typically played in the progression phase made it very difficult for them to immediately cluster in a group of four and win the ball back as soon as losing it.

It was not a lack of will, energy or effort that made England more ineffective in their pressing; but a lack of structure both in and out of possession created too big a gap between England’s players in the transition stage (the moment in the game when you lose or regain the ball).

5. Unbalancing the backline

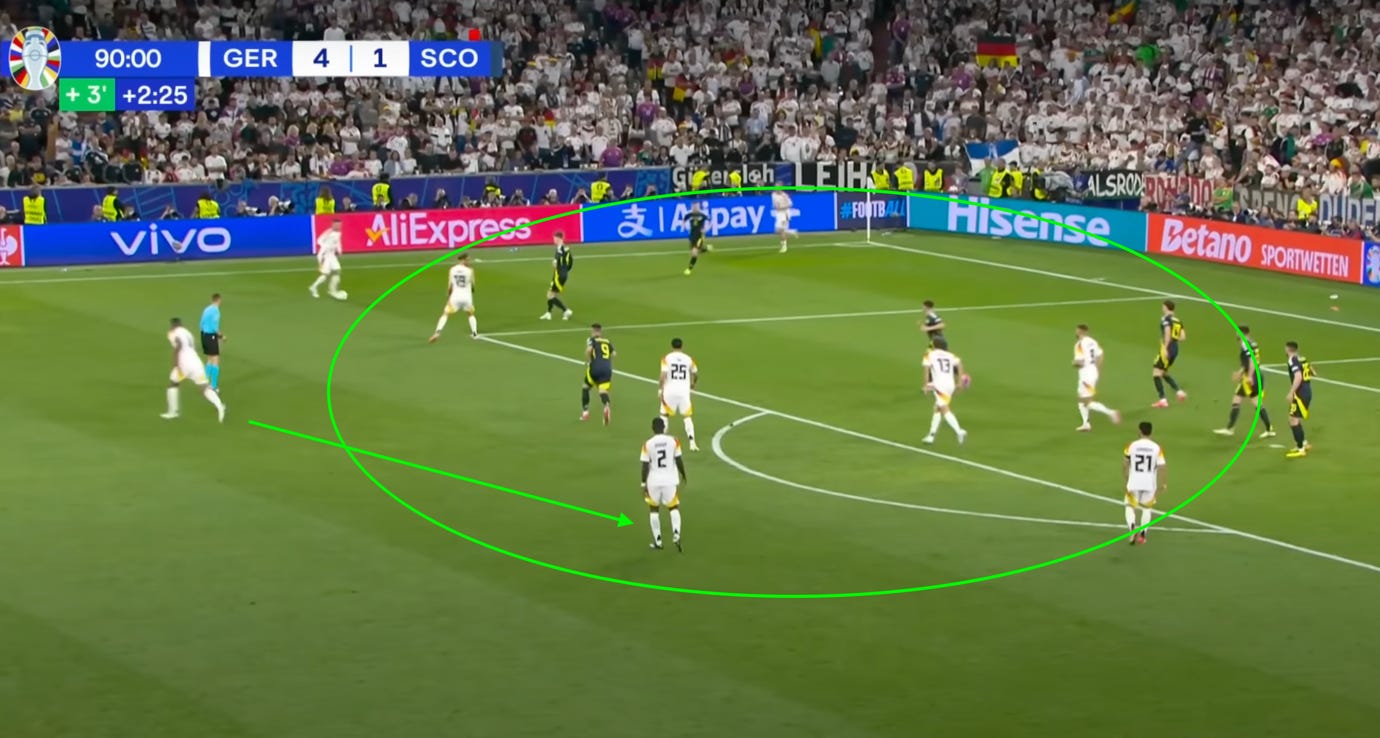

(Germany’s extreme box occupation against Scotland)

When asked about his coaching philosophy, Julian Nagelsmann once made the point that:

‘while most coaches want to unbalance the opponent in the midfield, I want to destabilise their defensive line’.

What is remarkable about this image here is not just how many German players are clustered in their close offensive positions. Look how vertically compact they are in the build-up. Both centre-backs, Jonathan Tah and Antonio Rudiger are almost playing as offensive 8s.

On a technical level, this principle is the simplest to explain. If the opponent defends with a back five, you stick six or even seven men on their defensive line. It is then the role of the midfielders to find the spare man. This is something England failed to do until the Netherlands game.

(Slovenia’s defensive overload against England)

This is simply one of dozens of examples I could have chosen. England are at a one-man disadvantage here. While they are attacking a back line of four, they only have three men planted, with two making late runs. This is far too conservative an approach to unbalance a deep block. England should have planted five players on the back line, with two late runners contributing to more chaos.

Yet there is one final feature of this principle that defies all that has been written before. Unleashing chaos. Both Spain and Germany were able to do this to perfection.

Yamal’s magnificent goal would not have been possible without the freedom he was given to ‘smell’ the moments in the attacking phase and break out of his role as a width-creating right winger. While most pundits focussed on the technique of his shot (remarkable, yes), for me it was the intelligence of his movement into this space that created the opportunity for an epoch defining goal.

(Musiala being given freedom against Scotland)

Musiala here vacates his central position into the left offensive space where theoretically the right full back should have been. This is not a system error, but the German players embracing the chaotic element of offensive play. While nine outfield players (even Toni Kroos) had to adhere to strict positional constraints, the effectiveness of positional play was only unleashed to its full, devastating potential when special talents were allowed to violate it.

We are now entering the territory of post-positional football. In the words of the philosopher, Ludwig Wittgenstein, it is time to throw away the ladder. His reflections on the futility of pure analytic philosophy are just as relevant to describing the futility of a purely positional play orientated approach.

My propositions serve as elucidations in the following way: anyone who understands me eventually recognizes them as nonsensical, when he has used them—as steps—to climb beyond them. (He must, so to speak, throw away the ladder after he has climbed up it.)

He must transcend these propositions, and then he will see the world aright.

For many aficionados of modern football tactical theory, this is perhaps the most important point in the piece. The penultimate and final actions in the box are what separates great teams from champions. It’s indeed what separated Spain from Germany in that thrilling Quarter Final. Freedom. There is plenty of discussion about this in coaching circles – the term ‘relationism’ being attributed to the freedom coaches are beginning to give players within positional play frameworks. Xabi Alonso’s use of Florian Wirtz at Bayer Leverkusen or Pep Guardiola’s use of that Argentinian number ten in his Barcelona team are prime examples of freedom manifesting within a rigid structure.

The structure serves as a means to an end. The end is to release creativity. It is the one thing positional play cannot impact – devastating moves in the final third. To quote the Wittgenstein of football, Pep Guardiola himself:

‘It is my job to get you to the final third, it is your job to finish it’.

In order to become truly dominant at the business end of tournaments, England needs to find a way to release the creativity of their great individual talents. But not until the foundations have been laid.

So, what is to be done?

Adhering to the five principles I have outlined does not determine the game model, system or tactics England uses. Whoever the next coach will be should have the autonomy to craft his own game model. Systems and tactics are something distinct from game methodology. Tactics are the products of incremental adjustments to the game situation such as personnel changes (Watkins for Kane, for example), formation changes (choosing to play with a back three, instead of a back four against a front two to be able to play out from the back) or playing approach (mid-block for a more reserved approach against a stronger team, a high block against a weaker team).

The sum of these tactics is the system. Take Spain and Germany, who both adhere to positional play methodology, yet do completely different things within it. Tactical changes and system building must not be confused with figuring out the overarching game methodology. Gareth Southgate and Steve Holland were top tacticians and good system builders. But what England needs now is a methodological overhaul. As Arrigo Sacchi, one of the intellectual architects of positional play and arguably the greatest football tactician of all time argued:

‘Great clubs have had one thing in common throughout history, regardless of era and tactics. They owned the pitch, and they owned the ball. That means when you have the ball, you dictate play and when you are defending, you control the space’.

In 2013, Gareth Southgate and Dan Ashworth unveiled the England ‘DNA’ scheme. It was an attempt to craft a defined playing style, an identity, and a clear game concept for the National Team. The FA had rightly identified that this was what England had been lacking in tournament football. Ashworth argued that England national teams at all levels need to ‘intelligently dominate possession, selecting the right moments to progress and penetrate’ in possession. Against the ball, England ought to ‘intelligently regain possession as early and efficiently as possible’. These goals are absolutely aligned with what the elite teams in the modern game are doing. Yet apart from the Netherlands game, we saw almost the antithesis of this on the pitch in the Euros.

(England’s former Technical Director Dan Ashworth, alongside a fresher-faced Gareth Southgate, c. 2014).

The fact of the matter is football has moved on from 2014. The way in which those two clear objectives have been achieved has changed. Football tactical cycles evolve every four to five seasons. They are primarily (but not exclusively) shifted by the actions of and reactions to Pep Guardiola. There is too slow a lag time between said tactical evolutions emerging at the club level, and the England National Team adopting them. There has been very little evolution in England’s game model since 2018. But there have been paradigm-shifting evolutions in global football ever since.

My next piece will moot how a series of executive-level reforms from the sporting side of the FA can bring about this shift in a generation. There is no reason why the ‘Silver Era’ of England can turn into a genuine ‘Golden Era’. The German FA’s reforms in the wake of the 2002 World Cup, catalysed by Matthias Sammer’s appointment as DFB Technical Director should serve as inspiration.

I don’t want this reflection to end on a bitter note. England are in a far better position than Germany were in 2002. England has the best academy system in European football and the highest concentration of elite coaches in the Premier League. The hardest part of team building – having the necessary technical quality to play the way you want to play – is already there. Germany did not have this in 2002. There is much to be hopeful for – provided people in the right places reinvent England’s game once again for probably its most competitive era yet.

Matt Andersen

World class.

Very informative read it full very fascinating and interesting and seeing a different side and how tactical football is now a days